A clash over who should clean Exeter’s police boxes in the 1930s sparked a flurry of letters between Exeter City Police and the Post Office as they battled for months over who should take responsibility.

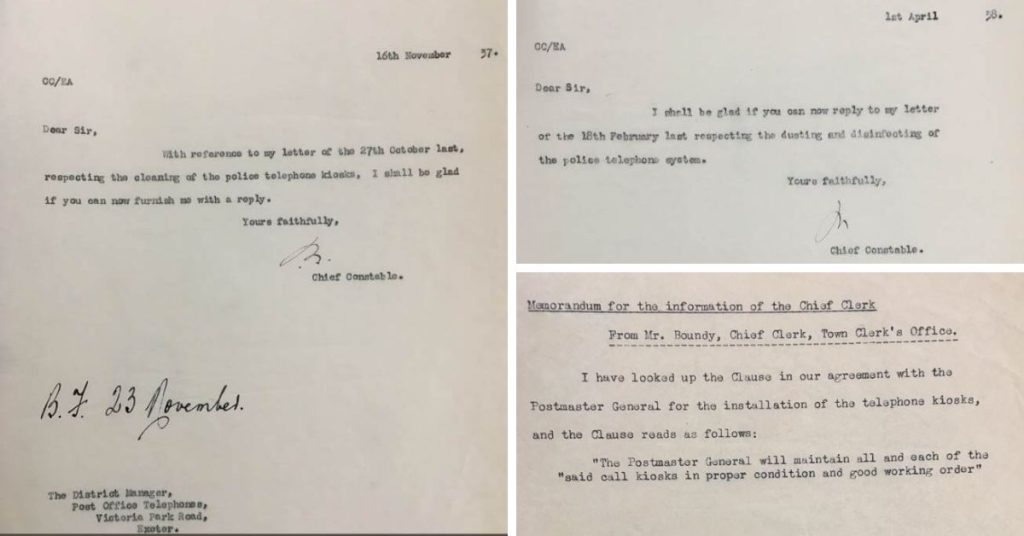

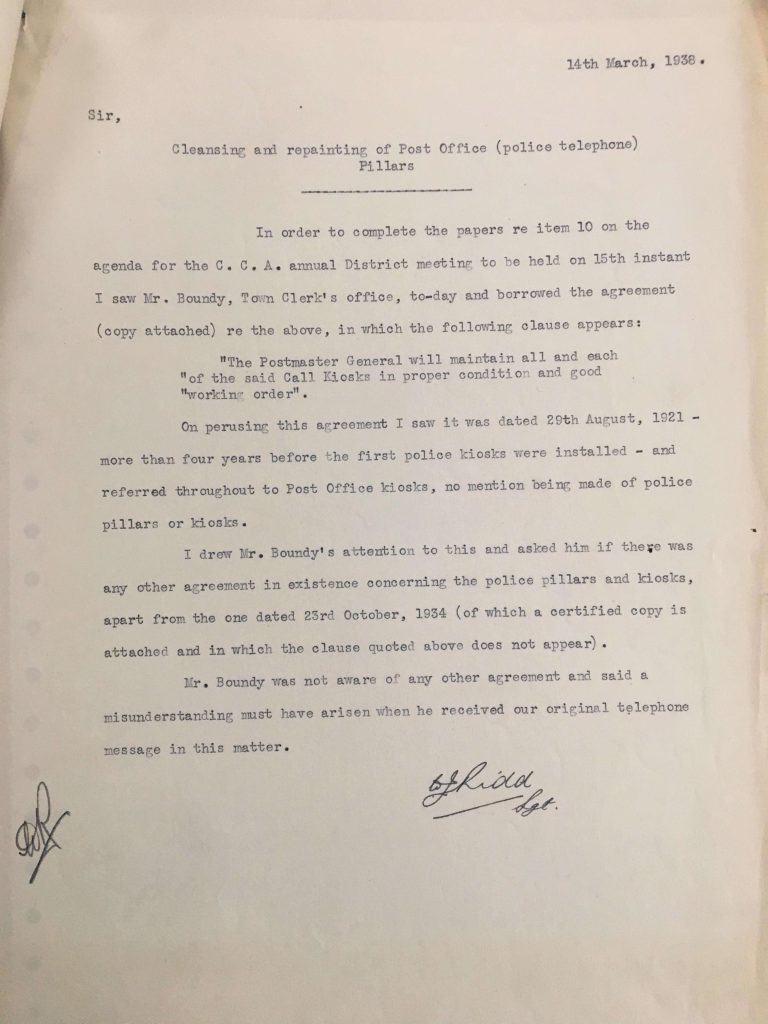

A file in the Museum’s archive at Exeter has revealed the cleaning row started in October 1937, when the Exeter City Police Chief Constable called for regular dusting and disinfecting by the Post Office of its police boxes and equipment, but requests were often ignored for weeks, prompting terse reminders.

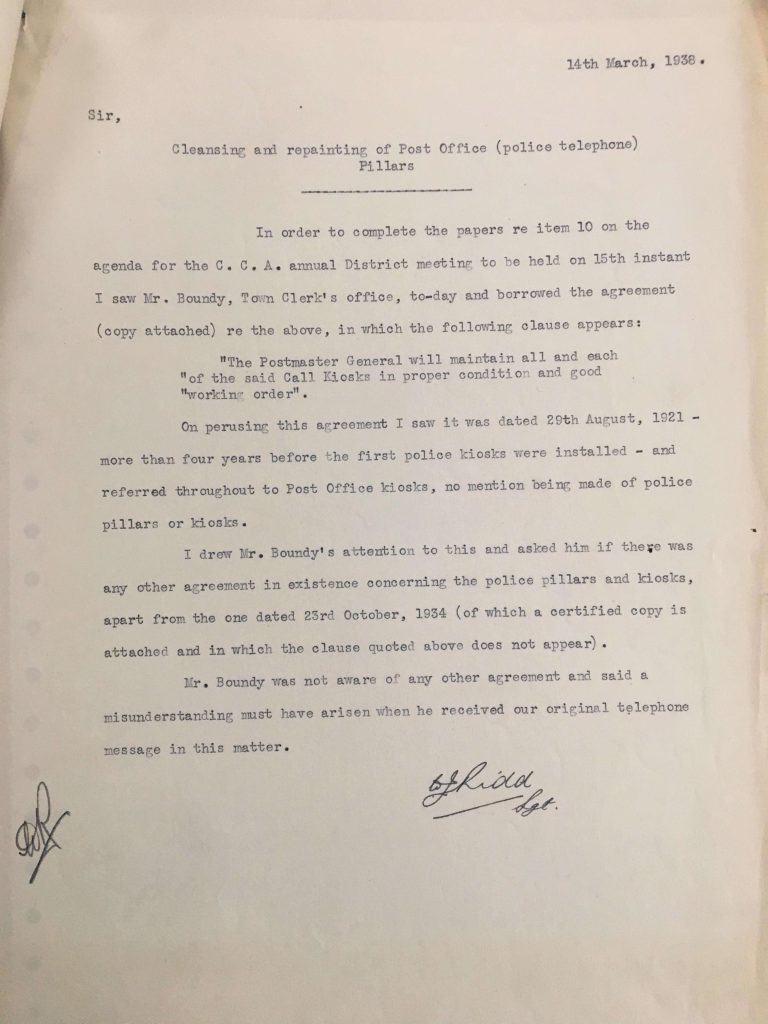

The dispute took several months to settle – and only after an agreement signed more than a decade earlier was produced as proof.

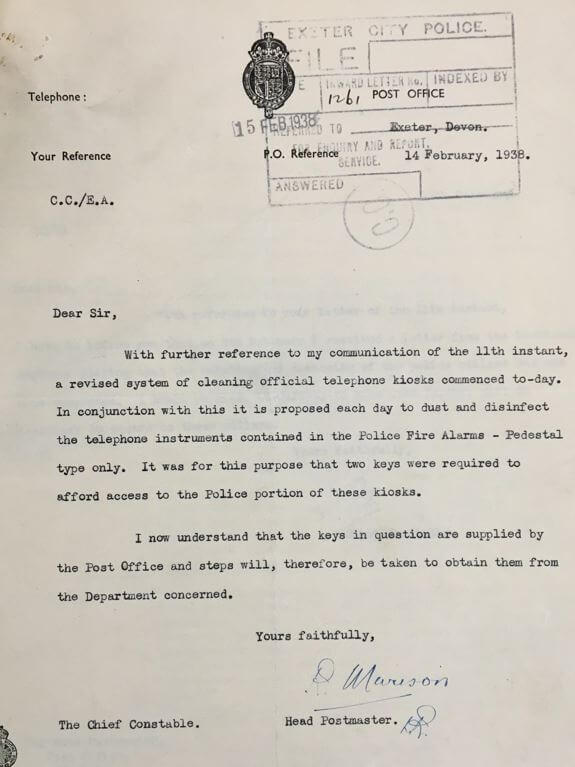

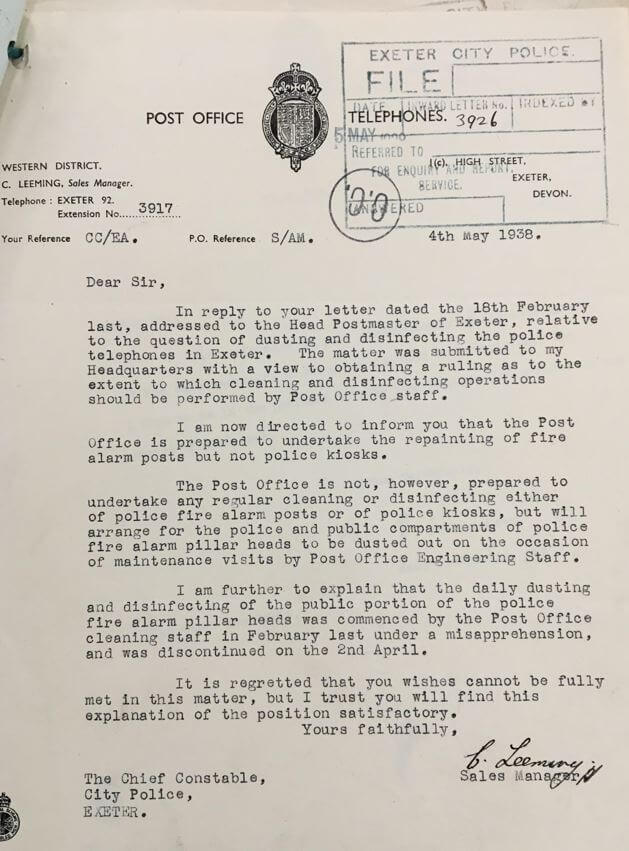

In February 1938, it was agreed two Post Office officers would daily dust and disinfect the telephone equipment, a service which lasted just three months when in May 1938 it pulled the service, washing its hands of responsibility for the upkeep of the police boxes.

The Post Office said the U-turn was the result of a mix-up in communications, adding it was ‘not prepared to undertake any regular cleaning or disinfecting’.

But in March 1938 it was forced to back down when an agreement was discovered dated August 29, 1921 – more than four years before the city’s first police boxes were installed – agreeing the Postmaster General ‘will maintain all and each of the said call kiosks in proper condition and good working order’.

The Town Clerk’s office for Exeter – who handed over the signed document – admitted the earlier snub had been a ‘misunderstanding’.

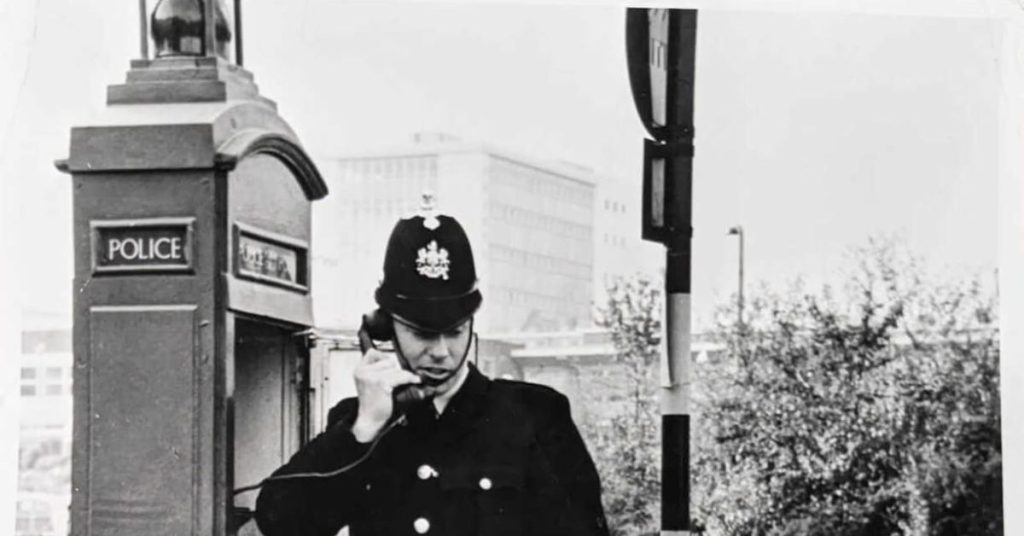

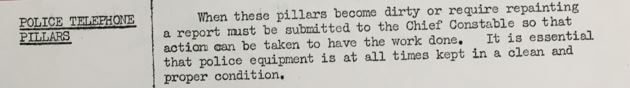

Police box and phone cleanliness concerns spilled over into Exeter City Police Daily Orders -instructions and commands to be obeyed – when on December 2, 1937, the Chief Constable demanded ‘essential’ equipment was ‘at all times kept in a clean and proper condition’.

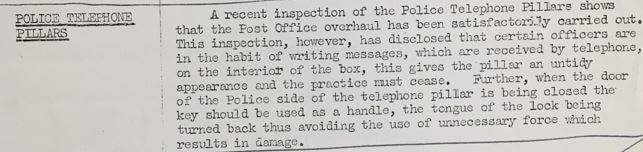

Weeks later, on February 12, 1938, following an inspection, he ordered officers to stop scrawling notes on the inside walls of the police boxes.

“Certain officers are in the habit of writing messages, which are received by telephone, on the interior of the box, this gives the pillar an untidy appearance and the practice must cease.”

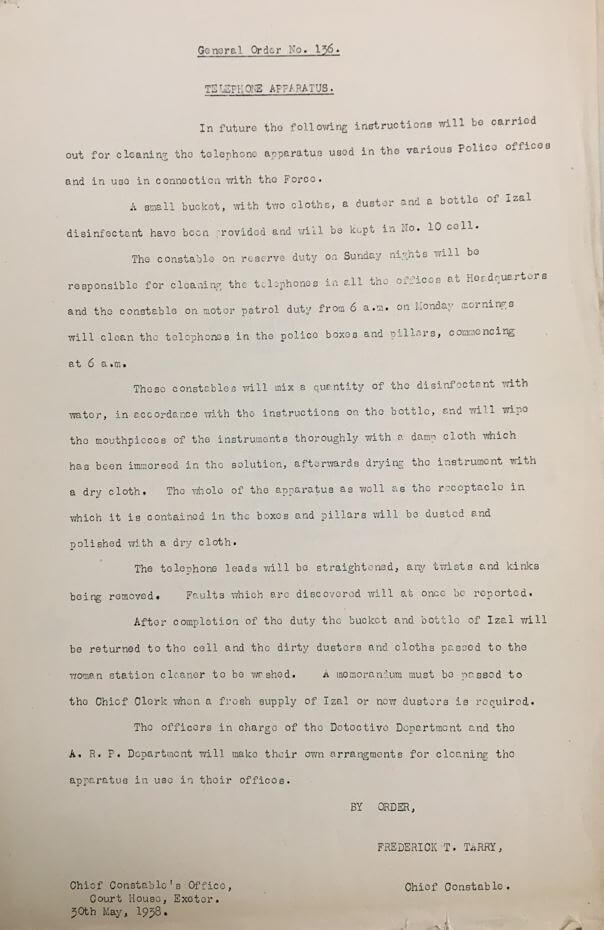

And the spotlight fell on the overall cleanliness of telephone apparatus used in police offices and by the force, as Chief Constable Frederick Tarry earmarked Sunday evenings for the Constable on reserve duty to disinfect every office telephone at headquarters.

He said Monday’s motor patrol Constable was responsible for cleaning all the telephones in police boxes and pillars, stating the chore should begin at 6am.

The Standing Order outlined strict instructions for cleaning the equipment, setting out the exact brand of disinfectant, where it was kept, how it should be used, going as far to instruct ‘telephone leads will be straightened, any twists or kinks being removed’.

The Standing Order states: “After completion of the duty the bucket and bottle of Izal will be returned to the cell and dirty dusters and cloths passed to the women station cleaner to be washed.”

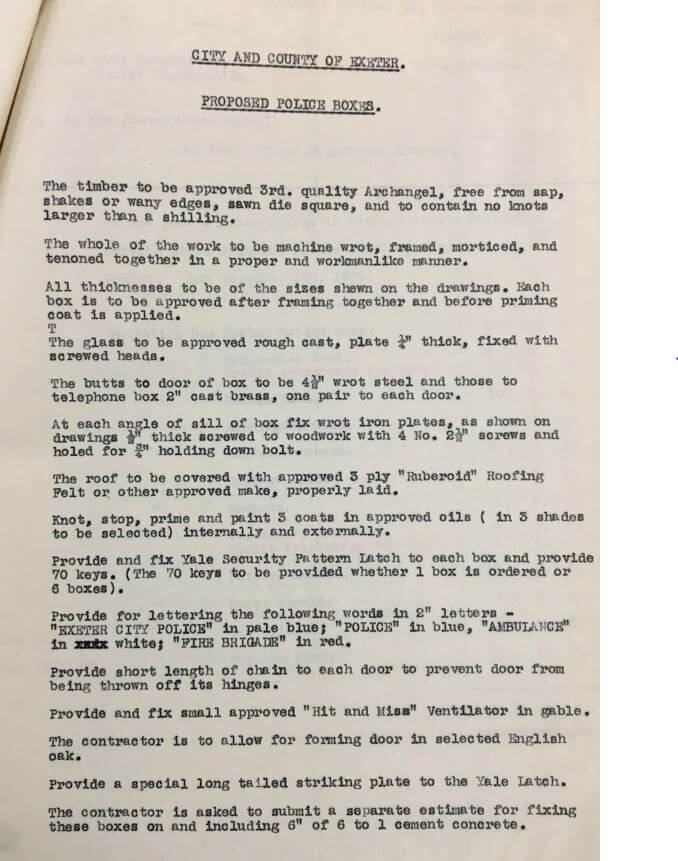

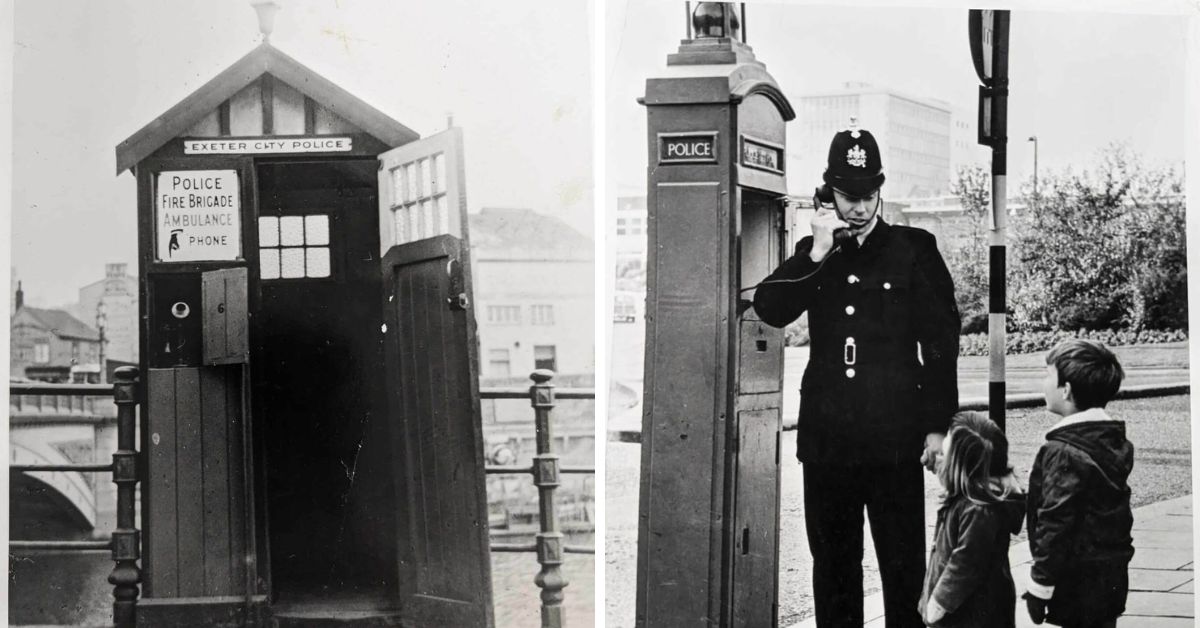

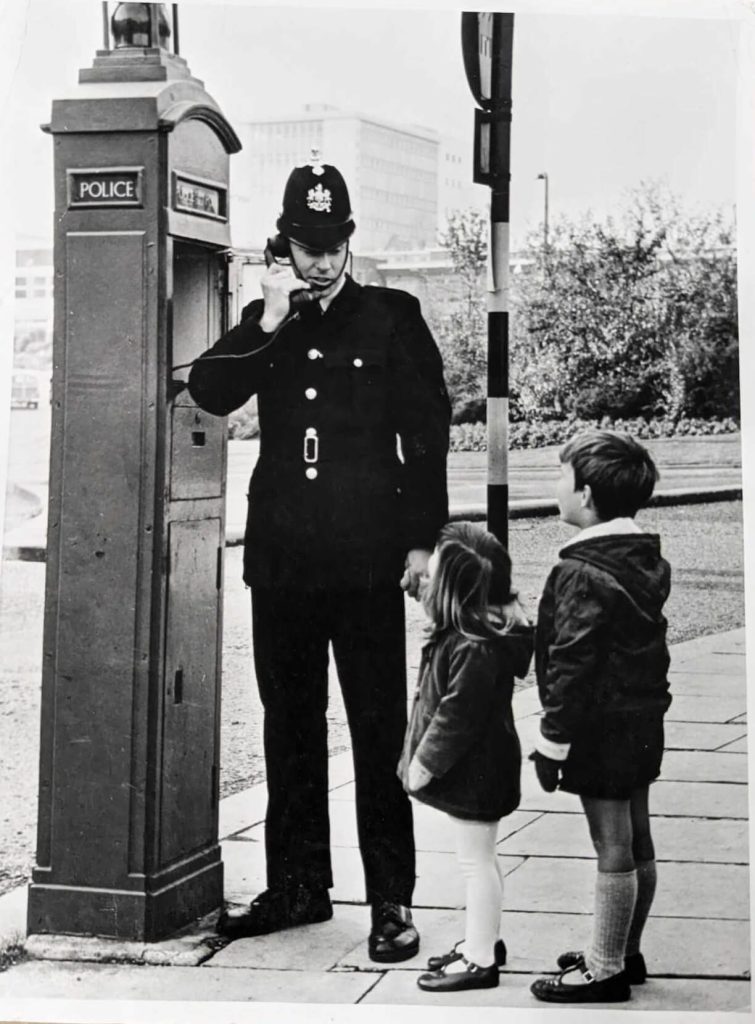

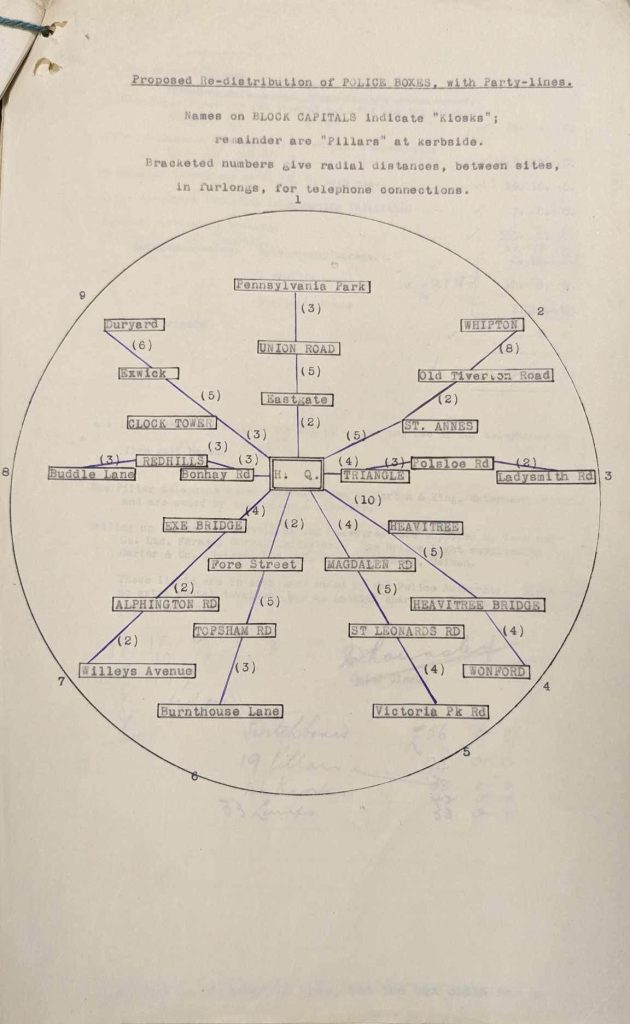

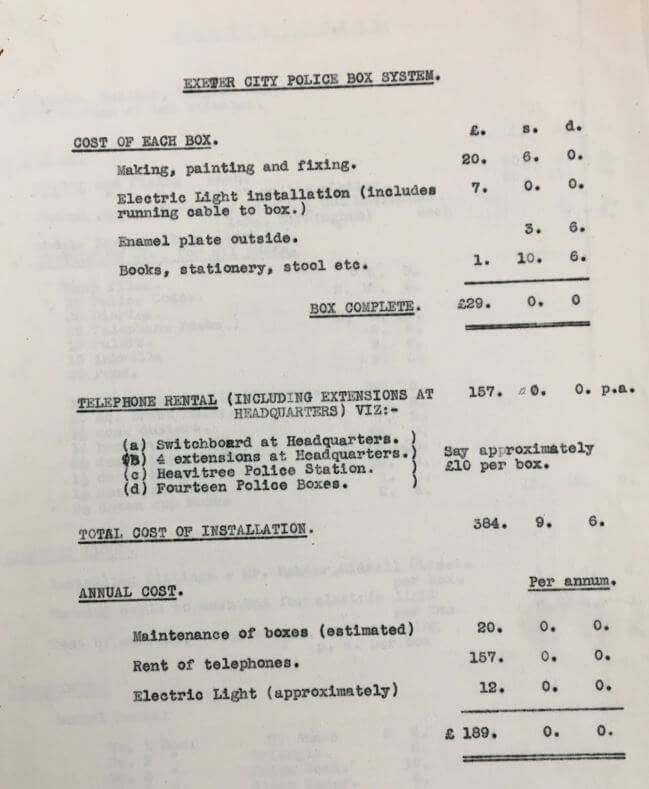

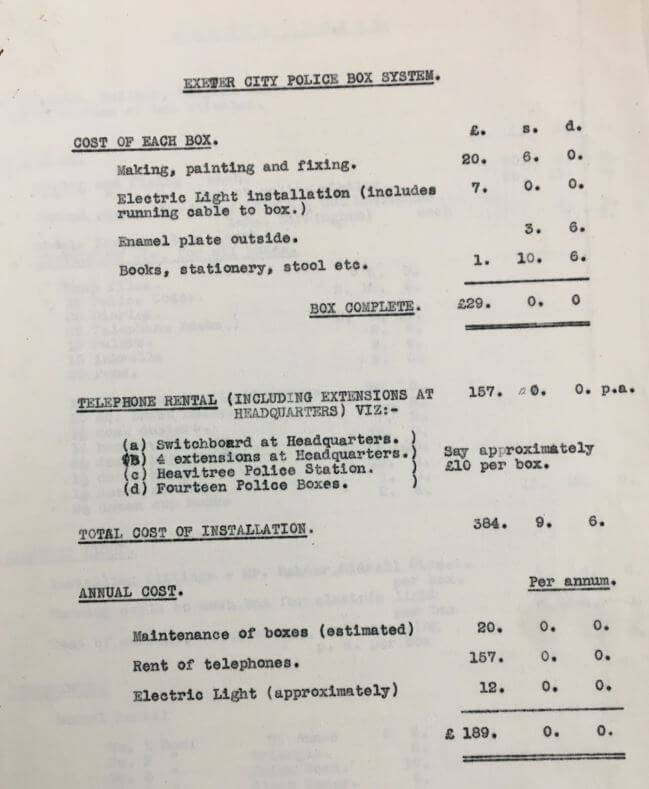

Exeter proposed 14 police boxes for the city, at a cost of £29 each to build and kit out.

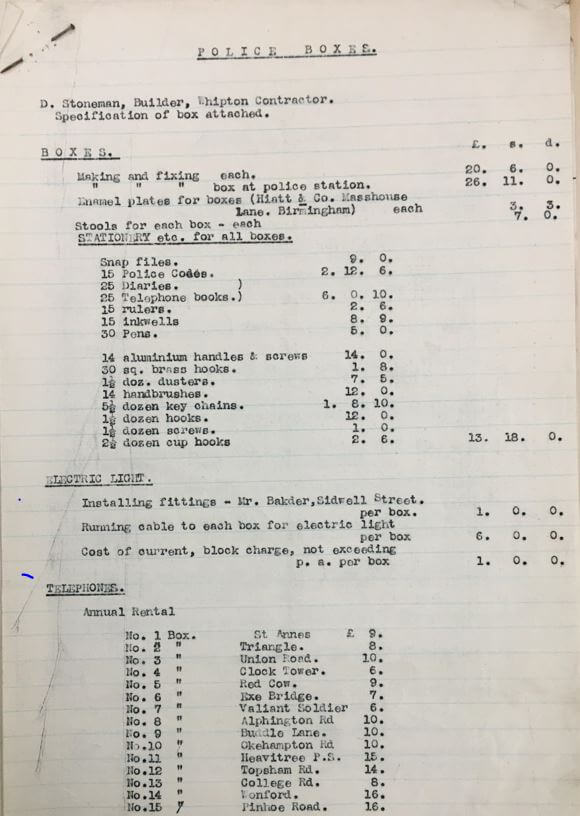

The wood to build each police box had to be ‘free from sap’ and any knots could be ‘no larger than a shilling’.

The locks on the boxes were Yale, the doors had to be made of English oak, and the police order stated 70 keys ‘if one box is ordered, or six’.

All police boxes were kitted out with stationary, diaries, telephone books, rulers, inkwells, and pens.

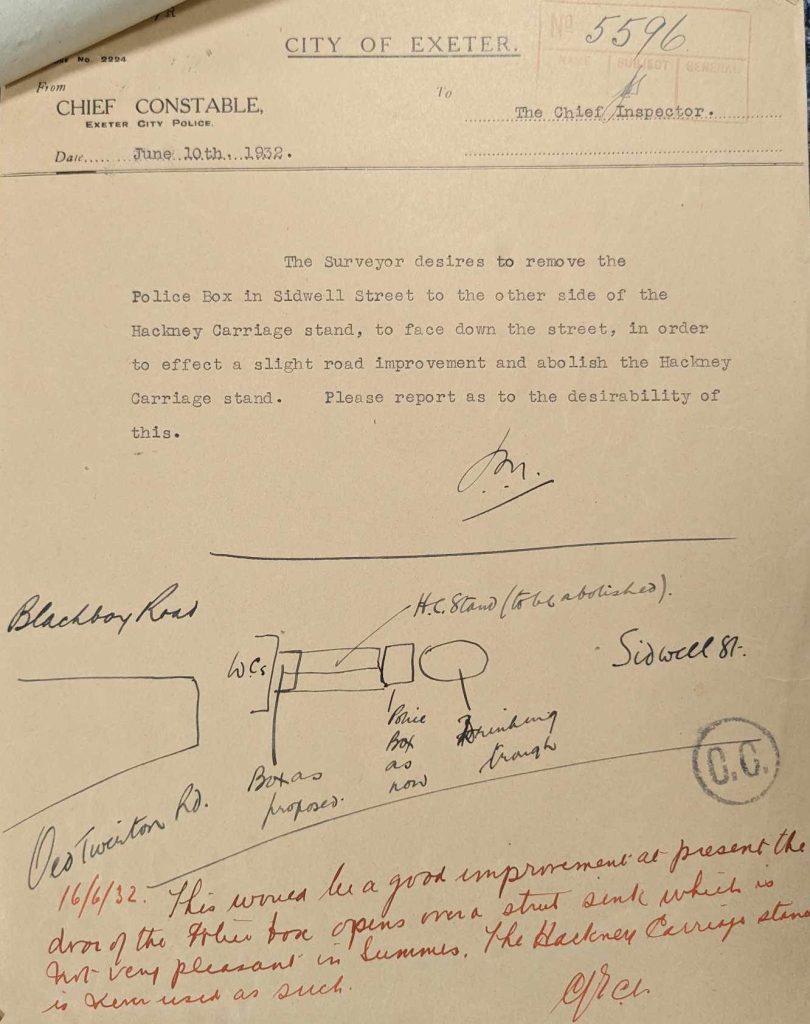

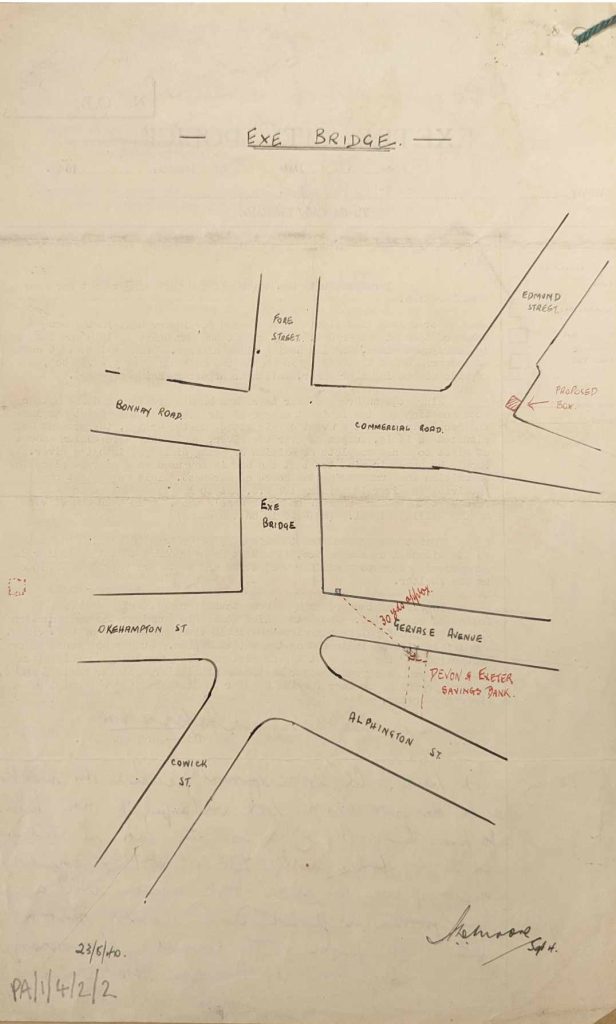

The areas of Exeter identified as suitable sites included the Clock Tower, Exe Bridge, Alphington Road, Buddle Lane, Okehampton Road, Heavitree Police Station, Topsham Road, College Road, Wonford, Pinhoe Road.

Documents held in the Museum archive at Exeter show the total cost of the telephone rental for 14 police boxes – including the switchboard at headquarters – was £384, nine shillings and six pence.