‘A Policeman’s Lot is Not a Happy One’, the well-known song from the Gilbert & Sullivan-penned operetta ‘The Pirates of Penzance’, also known as ‘A Slave to Duty’, could be a true statement of what the life of a constable in the Cornwall Constabulary was really like in the earlier years its existence.

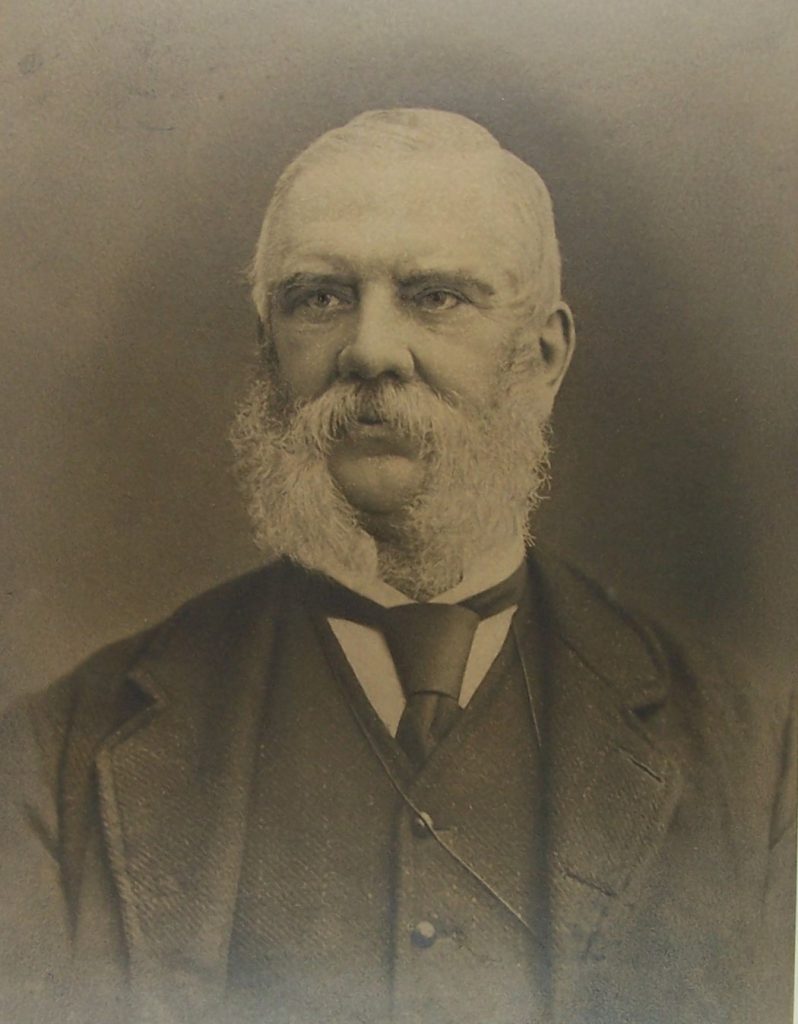

The first Chief Constable of Cornwall Constabulary was Colonel Walter Raleigh Gilbert, possibly a relative of W.S. Gilbert, the Victorian lyricist who wrote the song. We wonder at a possible conversation that could have provided the inspiration and try to understand the conditions that made a constable’s life such an endless grind as illustrated by that song.

‘The Pirates of Penzance’ is a comical opera, and the lyrics attempt to explain the Victorian policeman’s lack of freedom – against that of less law-abiding citizens!

It is probable that life in the other 200 plus Victorian police forces was very similar to that endured by Cornish policemen.

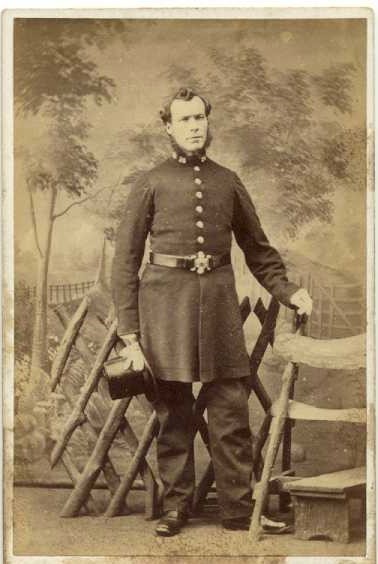

In 1888 The Cornwall Quarter Sessions (forerunners of the County Council) produced a set of rules governing the police in Cornwall. The Chief Constable of the Constabulary, City or Borough, presented every policeman with a printed book that contained the general rules of his employment, which strictly regulated his entire life.

A constable was expected to always wear his uniform when not at home. Except for a few days annual leave, he was not free to do as he wished, he was always at the ‘beck and call’ of his supervising officers and he was not allowed to leave his home, or the spartan accommodation provided for single men. These rules applied even if he had completed his 9-hour patrol duty for that day. It was suggested that policemen should pass their free time reading and learning the contents of the Rule Book.

If a man off duty wanted to leave his home to conduct his personal affairs, he required his Superintendent’s permission and had to apply in writing four days in advance. In 1912 national legislation gave policemen one day off in fourteen. This was no doubt popular with the Constables, but not so with the senior officers of the Cornwall Constabulary.

At first the Constables thought they were free to do what they wanted on that day. However, their freedom was short lived. The supervisors had very different ideas and new rules were soon issued. An officer was only allowed a day’s rest if there wasn’t a requirement for his services on that day. He was not to leave his home before 8am and had to be home by 10pm. If he served on a detached beat, the Superintendent’s permission was required to leave the area of that beat. When rest days were first introduced, if a Constable left his beat area, he was required to parade at the Divisional Station on his return to work. This could involve a punishing march of many miles in rural Cornwall, but to many officers’ relief this requirement was rescinded within months.

With the outbreak of the Great War in 1914, the men were expected to have the patriotic spirit to forgo the entitlement to a day off; it is reported that they all did so throughout the Great War.

Our feelings we with difficulty smother

In common with most other police forces, a Constable was not allowed to marry until permitted to do so by the Chief Constable. He had to provide full details of the social background of the proposed wife and her family. If approved, and a police house was available for them to occupy, the man was classified as being on ‘Married Strength’ and allowed his nuptials.

When Sir Hugh Protheroe-Smith was appointed as Chief Constable in 1909 it became even more difficult for a Constable to get married. Why?Simply because Chief Protheroe-Smith himself never married; we might assume that matrimony for his men might not have been high on his list of priorities.

In 1920, apparently 17 men were awaiting permission to marry and from 1925, around 30 men were informed they would not be granted permission to wed for about 4 years! Furthermore, no man with less than 4 years’ service should apply for permission to marry. They were ordered to continue living in single men’s quarters until married. This meant they could not see their intended wife without written permission – obtained 4 days in advance!

It wasn’t long before Constables were appearing before the Chief Constable on discipline charges of being absent from their stations without permission, probably courting their intended. However, although the Cornwall Constabulary had significantly increased in size the police housing infrastructure was slow to catch up.

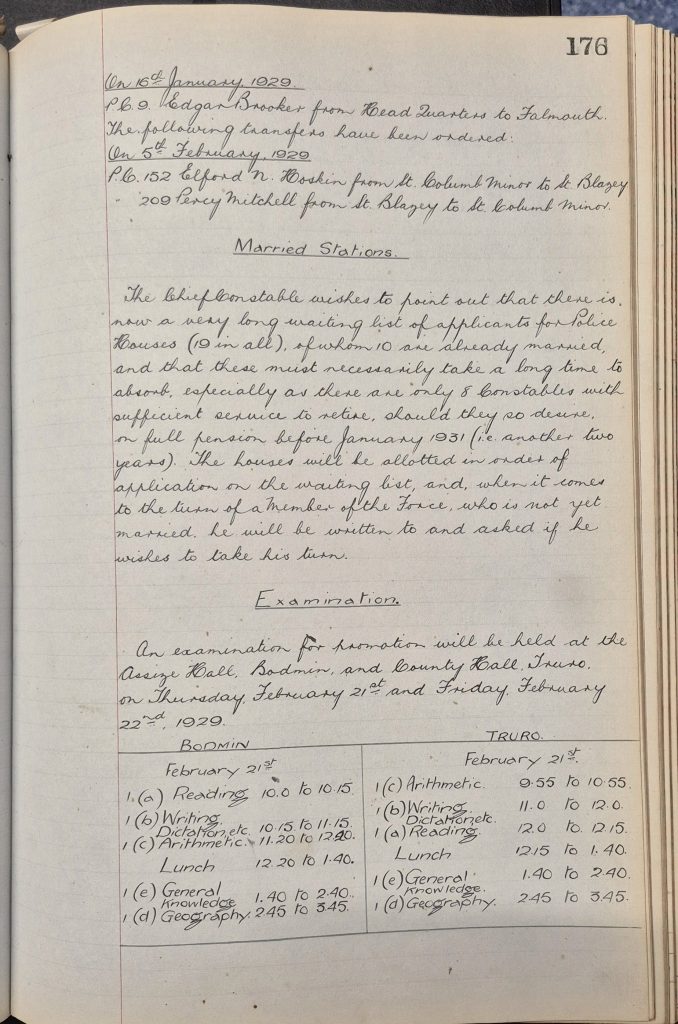

In the General Order in January 1929 (above), 19 constables were ‘on the wait list’ for police houses, of which 10 men were already married. The shortage of housing no doubt caused difficulties for newlyweds and wouldn’t have done much for morale. Cornwall Constabulary was increasing in size but the police housing estate was slow to catch up, which clearly frustrated Chief Protheroe-Smith.

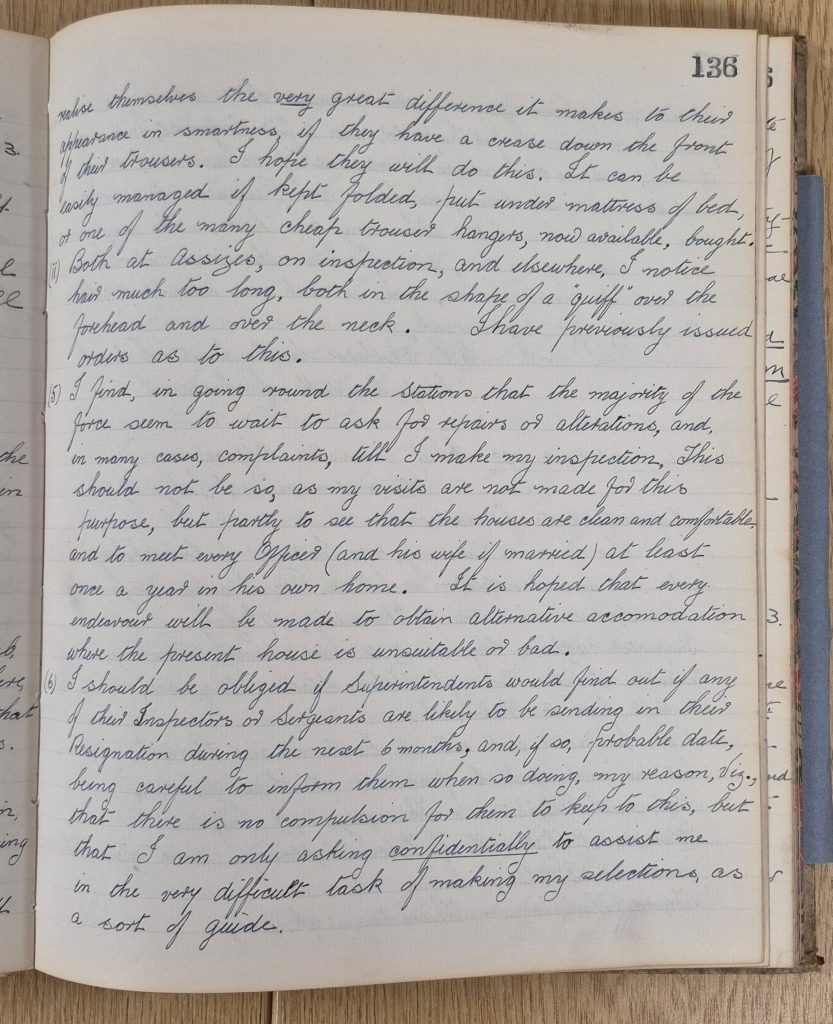

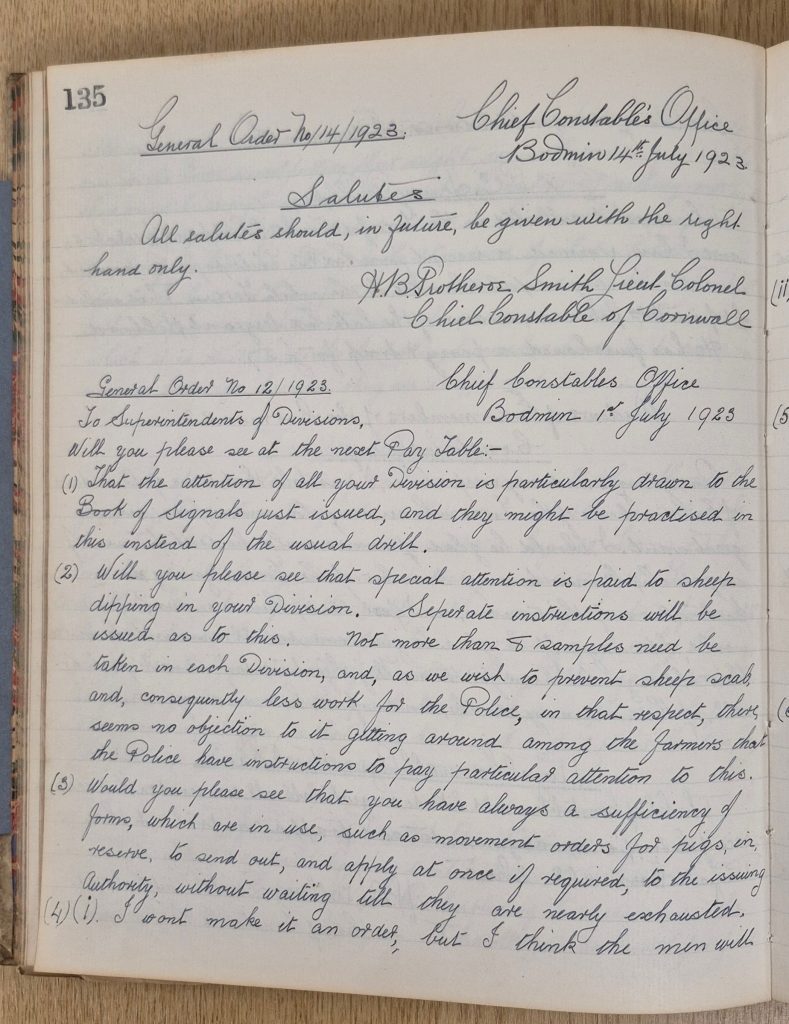

The Chief, being a military man, showed great concern with the appearance and bearing of his men. The practice of putting a crease down the legs of trousers, introduced in 1913, had reached Cornwall by the time the Chief returned from his recall to the Army for Great War duties. In a General Order of 1923, he issued his own directions below for getting good creases in trousers.

He was also concerned with saluting, advising the men always to use their right hand as seen in the General Order below. He also expected that men should stand to attention when giving evidence in Court. Haircuts also did not escape his notice, as well as visiting the police houses to meet policemen and their wives to ensure their homes were fit for purpose.

If a Constable decided that a policeman’s life was not for him, and left before he had (suffered?) six months of service, his outstanding pay was deducted on the pretext of paying for the alteration of his uniform, so it would fit his successor! If he quit the force without giving notice he could be arrested and taken before the justices, where he would face an imprisonment term of one month’s hard labour.

Before the creation of the National Health Service, all police officers were advised to join a Benefit or Friendly Society, to provide against expenses incurred through illness or accident. Sound advice, because the Police Authority being responsible for their employees’ health, deducted four shillings a day for ‘board and lodging’ from any officer requiring hospital treatment. A week in hospital would therefore cost 28 shillings from a wage of about 30 shillings, so a form of health insurance was essential.

His capacity for innocent enjoyment is just as great as any honest man

An essential qualification for a Cornwall Constable was ‘perfect sobriety’; with all the other regulations restricting his life, it would have been difficult to be anything else. Several men were recorded as being punished for ‘tippling’ or given advice about their drinking habits. Ron Peters, born in Saltash Police Station in 1927 and closely associated with Cornwall policing for almost 100 years, told us that ‘tippling’ was probably the charge given when a man had a drink when he was ‘off duty’.

On 31st August 1908, a Sergeant Fuller appeared before the Chief Constable charged with tippling – he was heavily punished by being reduced in rank to a Constable and transferred to another station at his own cost. This could mean moving from one end of the county to another, with family, transport costs etc.

In Chief Gilbert’s time this transcript is taken from his memoranda:

9th July 1871

PC73 Thomas Philp has been dismissed with forfeiture of a week’s pay for being drunk on duty.

PC158 William Davis has been fined £1 for being absent from his Conference Point and being drunk on duty.

That might go some way to explain the rule from 1888 onwards that a Constable was prohibited from visiting a public house ‘on any pretence whatever’. The rule suggests that if he requires refreshment and there is no other place he can obtain it, he should get the refreshment delivered to his home or the station. This same order instructed that he should never sit down in licensed premises.

Constables in detached stations were discouraged from ever drinking in any pub on their beat, and this policy persisted throughout the existence of the Cornwall Constabulary until 1967. By contrast, when Ranulph Bacon was appointed Chief Constable in Devon in 1947, the first disciplinary matter he was called to deal with was a police Constable charged with ‘playing darts and drinking beer’ in a Honiton pub. It is claimed that Chief Bacon asked the prosecutor where the man was supposed to drink!

Returning to the tenure of Chief Constable Protheroe-Smith, only one Cornwall Constable was disciplined for being drunk, whilst one Sergeant and four Constables were punished for other misconduct involving licensed premises.

Cornwall Constabulary Rule Book

Here’s a list of some of the pettiest regulations to be found in the Rule Book of the time (around 1900):

Members of the force are forbidden to play cards at a police station, or to meet elsewhere, to play cards.

No member of the Force is ever to be seen carrying an umbrella when on duty in uniform.

Officers were not allowed to use a bicycle to collect their pay from the Section station, meaning a walk of around 20 miles for the unlucky ones.

When on duty, and at all other times, a Constable was not allowed ‘on any pretence whatever’ to ride on any private or public conveyance, unless by express permission or direction of a superior officer (this rule applied also to cycles until about 1904).

The incursion of debts by a Constable was a disciplinary offence. They were also strongly advised, on threat of disciplinary proceedings, not to purchase anything on hire purchase terms.

New uniform garments only to be worn on Sundays until the following New Year.

Sunday was a special day in Cornwall, probably in respect to the strong traditions of Methodism in the county. Constables were expected, whilst on duty, to attend Divine Service each Sunday morning and evening. Their duty plan for the month included special detail for the Sundays to ensure they went to church.

All this makes us question why anyone would want to join the police back in the late 19th to the early 20th century, with the control exercised over them by their senior officers. But times were tough, with overwhelming poverty, strikes, and failed harvests causing widespread misery to the populace.

A policeman’s lot might not have been a happy one – but secure employment with a regular wage would have been a significant lure to men prepared to be a ‘slave to duty’.

Words by Peter Hincliffe 2018. Edited by Andrea Leggett 2025.